The Earle Liederman Story

Part Two

by Kenneth Terrell

I DID a little thinking; Liederman wasn't the only one in the business; I had taken other courses; maybe this desire to see him was only hero-worship, after all; I would look up some of the others.

I did meet several of the lesser-lights; disappointing; they were as dull as their courses had been, and in most cases they were only interested in selling me something further. I didn't like them. I liked them less when they all seemed jealous of Liederman; I always mentioned him and they all agreed that his course was pretty good; but -- he was just lucky; he had a good advertising man; he couldn't do half the things, the feats he claimed he could do; actually, he was only a figure-head; it wasn't his system anyway; there was no such person as Liederman. It all sounded like the gossip of plain, greedy envy to me.

I journeyed to Newark in quest of a meeting with Lionel Strongfort whose advertising seemed at the time, to place him as second in importance to Liederman; his office, however, was far from close in size, or in busy-ness. I failed too, in seeing him; but his secretary was generous in giving me a long interview; a lecture on physical culture; and - trying to sell me practically everything, including an interest in the business, itself.

In some cases my receptions were more satisfying, somewhat educational, and of sufficient inspiration to keep my enthusiasm alive. Professor Atilla, for instance; he ran a small weightlifting studio farther uptown. he had been an associate, a trainer, he said, of the Great Sandow; he showed me much interesting literature (proving his claims) on the Sandow career; and told me some interesting stories of his tours with that Immortal.

The Atilla studio, European style, was filled with a variety of exercising apparatus such as I never knew ever existed. There were bar-bells of various shapes, sizes, weights; with assorted thickness of bars; some with bent bars, some with hollow bars containing mercury which, when tried lifting the bell, would travel from one end to the other, causing the lifter to perform feats of balance not to be found in the book, any book, only to give up in failure and embarrassment, in each case. There were trick dumb-bells; kettle-bells; grip machines; Roman chairs; Roman Columns; and many other gadgets to delight any strength enthusiast. To visit Atilla was a joy; I went often and always left reluctantly, but with one of the Professor's interesting stories vivid in my mind; a newly discovered muscle, and a sore one to make the visit more materially memorable; and with inspiration acquired from watching his finely trained pupils perform; and from the Professor's instruction of them.

It was this little studio that Siegmund Klein later took over, enlarged and modernized, and moving to its present location, developed into the most unique place of its kind in this country; Klein's model of this type of Temple of Strength is the original from which most all our American weight-lifting studios are still being copied; Sig has gloriously promoted the Atilla-Sandow tradition in America. more than that, he has improved upon their methods; he has developed men who, like himself, have far surpassed the originals in all departments. Take a bow Sig. The Klein studio is the Mecca of all strong men, and would-be strong men, who visit New York; and in happy contrast to some of my early, cold receptions in the city, Siegmund Klein, as did his predecessor, Attilla, make everyone, friend or stranger, welcome.

I had been in New York for a month during which time as you will gather, I got around quite a bit and met many people in the muscle building game. I kept trying to contact Liederman to no avail. I kept looking others up and, as I said, some were interesting; others riled me. A side trip to Baltimore proved to have been one of my better inspirations; it brought about a meeting with Anton Matysek who still rates with me as one of the nicest and most amusing men I ever met in the pursuit of bigger and better muscles. His physique still stands out in my memory as one of the finest I ever saw; he could do things with his muscles too.

The Matysek system was by no means one of the lesser known of the mail order courses, rather, it was one of the more popular ones, certainly enough to keep him so busy that he had little time for seeing mere fans such as I; nevertheless, I was ushered in to his private office at once. He greeted me warmly if still, somewhat suspiciously; said he had been having complaints from some dissatisfied Terrell, he hoped I had no complaints to make. I had only take his muscle-control course and I assured him that I was more than pleased with that. Thereafter, we were friends.

He was kind enough to strip to the waist and show me his unexcelled upper body, and to give me a brief demonstration of muscle-control I was thrilled at his willingness to do all this; and impressed with his suppleness of muscle; his exceptional definition, all of which, he assured me, had been developed by weightlifting, muscle-control, and practicing his own system, which was a form of weight-lifting.

He invited me to try lifting a 250 pound bar-bell which he kept in his office. The bar was exceptionally thick, and I felt quite proud of myself to be able to dead-lift it. Then he, with amazing ease, cleaned and jerked it. Having never seen such a lift so easily performed, I was goggle-eyed at the man's power. But that was small potatoes compared with what came next.

He had me stand beside him, fold my arms, and stiffen my body and legs; then he reached across my chest, grasped my right arm just between the bicep and deltoid, with his left hand; with his right hand, he took my right leg, just inside the thigh. Then, rocking me over and across his chest, he pressed me to arm's length overhead I weighed 160 pounds and was as nervous and awkward as a wild mule; but it bothered him not at all. He, while keeping me at arm's length, arched backward, completing a full backbend and came to rest in a perfect neck-bridge. Then, after pressing me a couple of times, he arched upward, and forward, until his head came off the Boor; by now his back-bend was so close that his shoulders touched the biceps of his thighs. From this position it was no effort at all for him to continue to the erect standing position again; then, for good measure, he pressed me half a dozen times before he gently set me back upon my feet alongside him.

Later I saw Otto Arco perform this same feat while holding his partner in a hand-to-hand stand; but working with a trained, expert balanced in hand-to-hand, is one thing; handling such a clumsy ox as I was, is quite another. That Matysek was a MAN!

He was kind enough to ask me to have dinner and spend the night at his home; but the train I intended taking back to New York was nearly due, so I sputtered my thanks and hurried to the station.

Who knows upon reaching one of life's many cross-roads which is the better course to take? On the one hand we are lured by instinct and desire; on the other, by intellect and what we like to call 'common sense.' The latter, common sense, usually sides with safety, or what looks like it, and security, which may also be a jailer in disguise. The former, instinct, usually pleads its case thus: "Follow me, I make no phony promises; the road I suggest may be rough at times; no guarantees; but one thing you may be sure of, I will show you adventure."

On my way to the station in Baltimore it occurred to me that I was a lot nearer to home and the sort of safety and security I had known than I would be back in New York. And what the deuce was I after anyway? I wasn't quite sure about that any more. It had something to do with meeting Earle Liederman. Why? I had lost track of that too. But there must have been some reason; at any rate it was still a goal to be realized. Having had such a pleasant interview with Matysek was encouraging too. So--the battle was of short duration. Instinct won as it has in most instances where I have had a choice between the two courses. I still don't know whether my choice has been right in all instances; but when. I reflect on what has happened to me, and still does, in comparison with those I have known, who have always taken the other course--I'll keep on following instinct.

Back in New York--I was broke. Liederman would have to wait to have the pleasure of meeting me. It took some doing, but I found a job as, of all things, cashier-bookkeeper for a large corporation. What a spot for a muscle-man (in the making), no exercise at all, in the day-time, that is. Well, maybe I did a hand-stand on a desk and then; tore a telephone book or two; and lifted a stenographer. It wasn't until sometime after I left the company (voluntarily) that I learned that the boss had overseen a few of my little shows and had 'over-looked' them because he wasn't quite sure whether I would react physically, in case of a reprimand. Tch. tch, he could have taken me easily.

The office where I worked was only a few blocks from Liederman's. I had to pass his office daily, in fact, on my way to and from the bank. So, I would stop in every day or so and inquire for Mr. Liederman, no luck; Mr. Liederman was in Alaska; Mr. Liederman was in the Canadian Rockies; he was in California; in Atlantic City. What to do--evidently my approach was all wrong.

Then one day the idea just popped into my head: why not write him a letter, business-style? Instinct again. . . I got a stenographer to co-operate and we explained, on company stationery, all about how we made it a point to see our customers, large or small, for the good-will of the business, if for no other reason; and how could he do the same if he was never in his office, or, if he was, why didn't he? Or something along those general lines. I signed the letter with a flourish and it went into my company mail bag.

The next morning I had a telephone call from Mr. Liederman's personal secretary; could Mr. Terrell come to Mr. Liederman's office this afternoon after five?--Mr. Terrell could-and would!

How about that for the power of the printed word! It was an excited, thrilled, and no little stage-frightened young man who was ushered into the Liederman inner-sanctum after hours that afternoon. It couldn't be happening; but it was, I knew because I pinched myself and could still feel it. My eyes were good; and they saw the man standing there, the same man they'd seen in photographs swing at them (my eyes) so many hundreds of times.

I was snapped out of it immediately by an out-stretched hand, and : "Hello, Ken, I'm glad to see you. Sorry you had some difficulty finding me in." I stammered some kind of acknowledgment, then: "You sure must have been having quite a trip for yourself." He replied: "Well, yes we have, you see, Mrs. Liederman and I have never been able to get away together for any length of time before; so we decided to make a summer of it seeing some of the places we've always wanted to see."

I had, in my fog, noticed the very attractive young woman sitting across the office, near the window, but had been in no condition for anything to, register very well. I wasn't entirely out of it yet, I said, "Mrs. Liederman?" He, "Why yes." Then he took me over and introduced me. She was as charming as she was attractive. And there I went into another partial blackout. But they both talked me out of it -- and I felt completely at home in a few minutes.

I had been wrong. I had thought that all the Liederman employees had told me as to his various whereabouts had been mere evasions to protect a busy man; now he was enthusiastically showing me a pile of snapshots he and Mrs. Liederman had taken on the trip. When I'm wrong, I apologize. I understand that some people find it hard to admit they are wrong. Why? It doesn't help, and the apology usually ends it with no mental cob-webs left over. I apologized and was again put at my ease.

Liederman wore a short-sleeved sport shirt. No stripping was, necessary to see that his photographs were honest. His arms were terrific in every movement. The outline of his pectorals showed through his shirt-front to round off his otherwise deep chest to perfection. I was impressed with the spread of his latissimus; from narrow hips and small waist width, the 'V' was there with no effort at tensing or spreading the shoulder blades. His neck, however, was, and still is the first and most noticeable feature of his development. He believes the neck to be, even more than the legs and back, the foundation of a good physique; the keystone to strength. "Start at the top and work down," he says, "develop the neck (the easiest part of the body to develop) first; then bring the rest of the body up to match and you have it." Simple, isn't it? Well, if that theory is true -- and I am inclined to agree-in fact, who am I to argue with him? Then, I still don't want to tangle with him.

More than any single feature however, I was impressed with the whole man: no general ever had better posture; yet, no sleeping baby ever seemed more relaxed.

(Continued Next Month)

PHOTO CAPTIONS

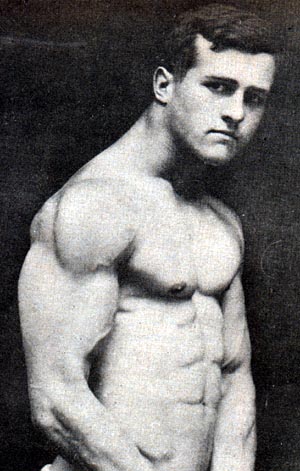

- EARLE LIEDERMAN An old photo taken and used during vaudeville days, eight years of which ended in 1918.

- EARLE LIEDERMAN At nine or ten years of age. Just an ordinary boy with an innocent mind. How and why I secured and posed in that Civil War Soldier hat will have to remain a mystery. The lapel button probably was an election campaign propaganda reading, "Vote for Grover Cleveland."

- EARLE LIEDERMAN From an old photo taken when about 17 years of age.

- EARLE LIEDERMAN snap shot taken when about 15 years of age. The arms then measured about 14 inches.